When Does The Number Of Electoral Votes Change

The Changing Racial and Ethnic Composition of the U.Southward. Electorate

The upcoming 2020 presidential election has drawn renewed attention to how demographic shifts across the The states have changed the composition of the electorate.

For this data essay, we analyzed national and state-level shifts in the racial and ethnic makeup of the United States electorate between 2000 and 2018, with a focus on key battleground states in the upcoming 2020 election. The analysis is primarily based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau's American Customs Survey and the 2000 U.S. decennial demography provided through Integrated Public Utilize Microdata Series (IPUMS) from the University of Minnesota.

Run across here to read the data essay's methodology for farther details on our information sources.

Eligible voters refer to persons ages 18 and older who are U.S. citizens. They make upwards thevoting-eligible population orelectorate. The termseligible voters,voting eligible,the electorate andvoters are used interchangeably in this study.

Registered voters are eligible voters who have completed all the documentations necessary to vote in an upcoming election.

Voter turnout refers to the number of people who say they voted in a given election.

Voter turnout rate refers to the share of eligible voters who say they voted in a given ballot.

Naturalized citizensare lawful permanent residents who accept fulfilled the length of stay and other requirements to become U.S. citizens and who have taken the adjuration of citizenship.

The termsLatino andHispanic are used interchangeably in this study. Hispanics are of whatever race.

References toAsians,Blacks andWhites are single-race and refer to the non-Hispanic components of those populations.

Battlefield states include Arizona, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. These states were identified by Pew Research Center using ratings from a multifariousness of sources, see the methodology for more details.

In all fifty states, the share of non-Hispanic White eligible voters declined between 2000 and 2018, with ten states experiencing double-digit drops in the share of White eligible voters. During that same menstruum, Hispanic voters have come to brand up increasingly larger shares of the electorate in every country. These gains are peculiarly large in the Southwestern U.S., where states like Nevada, California and Texas have seen rapid growth in the Hispanic share of the electorate over an xviii-year catamenia.i

These trends are also especially notable in battlefield states – such as Florida and Arizona – that are likely to be crucial in deciding the 2020 election.2 In Florida, two-in-x eligible voters in 2018 were Hispanic, virtually double the share in 2000. And in the emerging battlefield state of Arizona, Hispanic adults made up nearly one-quarter (24%) of all eligible voters in 2018, up eight percentage points since 2000.

To exist certain, the demographic composition of an expanse does not tell the whole story. Patterns in voter registration and voter turnout vary widely past race and ethnicity, with White adults historically more probable to be registered to vote and to turn out to vote than other racial and indigenous groups. Additionally, every presidential election brings its ain unique gear up of circumstances, from the personal characteristics of the candidates, to the economy, to celebrated events such every bit a global pandemic. Yet, agreement the irresolute racial and ethnic composition in key states helps to provide clues for how political winds may shift over fourth dimension.

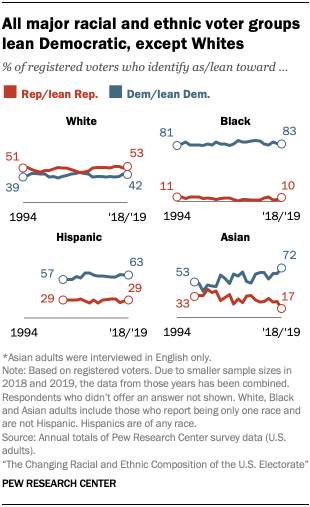

Black, Hispanic and Asian registered voters historically lean Autonomous

The ways in which these demographic shifts might shape electoral outcomes are closely linked to the distinct partisan preferences of different racial and ethnic groups. Pew Research Heart survey information spanning more than two decades shows that the Autonomous Political party maintains a wide and long-standing reward among Black, Hispanic and Asian American registered voters.three Among White voters, the partisan balance has been generally stable over the by decade, with the Republican Party property a slight advantage.

National leave polling data tells a like story to partisan identification, with White voters showing a slight and fairly consistent preference toward Republican candidates in presidential elections over the final twoscore years, while Black voters accept solidly supported the Democratic contenders. Hispanic voters have also historically been more probable to support Democrats than Republican candidates, though their support has not been every bit consequent every bit that of Black voters.4

These racial and ethnic groups are by no means monolithic. There is a rich diversity of views and experiences within these groups, sometimes varying based on country of origin. For example, Pew Research Heart's 2018 National Survey of Latinos found that Hispanic eligible voters of Puerto Rican and/or Mexican descent – regardless of voter registration status – were more likely than those of Cuban descent to identify equally Democrats or lean toward the Autonomous Party (65% of Puerto Rican Americans and 59% of Mexican Americans vs. 37% of Cuban Americans identified as Democrats). A bulk of Cuban eligible voters identified every bit or leaned toward the Republican Party (57%).

Among Asian American registered voters, there are also some differences in party identification by origin grouping. For instance, Vietnamese Americans are more likely than Asians overall to identify as Republican, while the contrary is true among Indian Americans, who tend to lean more than Democratic.

Given these differences within racial and ethnic groups, the relative share of unlike origin groups within a specific state can impact the partisan leanings of that state's electorate. For instance, in Florida, Republican-leaning Cubans had historically been the largest Hispanic origin group. Nevertheless, over the by decade, the more Democratic-leaning Puerto Ricans have been the state's fastest-growing Hispanic-origin group, and they now rival Cubans in size. At the same time, in states similar California and Nevada, Mexican Americans, who tend to lean Democratic, are the ascendant Hispanic origin group.

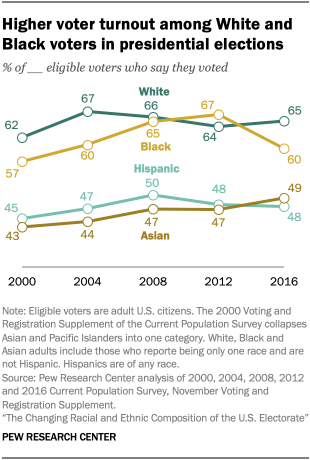

Partisan alignment does not tell the whole story when it comes to voting patterns. Voter turnout rates – or the share of U.South. citizens ages xviii and older who bandage a election – also vary widely across racial and ethnic groups. White adults historically have had the highest rate of voter turnout: About ii-thirds of eligible White adults (65%) voted in the 2016 election. Black adults have too historically had relatively high rates of voter turnout, though typically slightly lower than White adults. There was an exception to this blueprint in 2008 and 2012, when Black voter turnout matched or exceeded that of Whites. By contrast, Asian and Hispanic adults accept had historically lower voter turnout rates, with near half reporting that they voted in 2016.

White and Black adults are also more likely than Hispanic and Asian adults to say that they are registered to vote.

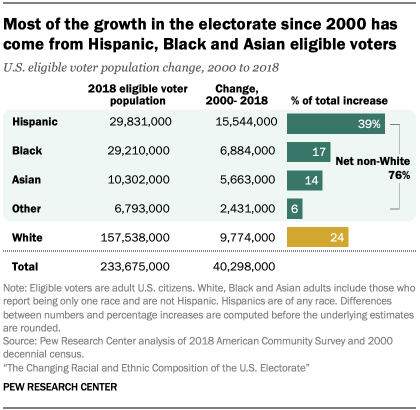

Non-White eligible voters accounted for more three-quarters of total U.Southward. electorate growth since 2000

The non-White voting population has played a large role in driving growth in the nation's electorate. From 2000 to 2018, the nation's eligible voter population grew from 193.4 million to 233.7 million – an increase of 40.3 million. Voters who are Hispanic, Blackness, Asian or another race or ethnicity deemed for more than than three-quarters (76%) of this growth.

The substantial percentage betoken increase of voters who are not White as a share of the country'southward overall electorate was largely driven past second-generation Americans – the U.Due south.-born children of immigrants – coming of historic period, as well every bit immigrants naturalizing and becoming eligible to vote. The increase has been steady over the past 18 years – from 2000 to 2010, their share rose by 4 percentage points (from 24% to 28%), while from 2010 to 2018, their share further grew by 5 points (up from 28% to 33%).

Hispanic eligible voters were notably the largest contributors to the electorate'southward rise. They lonely accounted for 39% of the overall increase of the nation'south eligible voting population. Hispanic voters made upwards thirteen% of the state'south overall electorate in 2018 – nearly doubling from 7% in 2000. The population's share grew steadily since 2000, with similar percentage betoken growth observed between 2000 and 2010 (3 points) and 2010 and 2018 (3 points).

The Hispanic electorate's growth primarily stemmed from their U.S.-born population coming of historic period. The 12.4 million Hispanics who turned eighteen between 2000 and 2018 accounted for eighty% of the growth amidst the population'southward eligible voters during those years. The group's sustained growth over the past ii decades will brand Hispanics the projected largest minority group amongst U.S. eligible voters in 2020 for the kickoff time in a presidential election.

Asian eligible voters likewise saw a significant rise in their numbers, increasing from 4.half dozen million in 2000 to 10.3 meg in 2018. And similar to Hispanics, their well-nigh two-decade growth has been relatively consistent. The population's share in the electorate grew at similar rates from 2000 to 2010 and from 2010 to 2018 (1 bespeak each). In 2018, Asian eligible voters made up four% of the nation'south electorate (upwardly from ii% in 2000), the smallest share out of all major racial and ethnic groups. Naturalized immigrants – a group that makes up two-thirds of the Asian American electorate – are the main driver of the Asian electorate'south growth. From 2000 to 2018, the number of naturalized Asian immigrant voters more than doubled – from iii.iii one thousand thousand to 6.9 1000000 – and their growth solitary deemed for 64% of the overall growth in the Asian electorate.

Despite notable growth in the non-White eligible voter population, non-Hispanic White voters still made upwardly the large majority (67%) of the U.S. electorate in 2018. However, they saw the smallest growth rate out of all racial ethnic groups from 2000 to 2018, causing their share to compress by nearly ten percentage points.

Shares of not-Hispanic White eligible voters accept declined in all 50 states

The overall reject in the shares of the non-Hispanic White eligible voter population tin can be observed beyond all states. (There hasn't been a decline in the District of Columbia.) While this trend is not new, it is playing out to varying degrees across the state, with some states experiencing particularly significant shifts in the racial and ethnic limerick of their electorate.

In total between 2000 and 2018, x states saw a 10 per centum point or greater decline in the share of White eligible voters. In Nevada, the White share of the electorate brutal xviii percentage points over virtually two decades, the largest drop among all 50 states. The decline in the White share of the electorate in Nevada has been fairly steady, with a comparable percentage signal decline observed between 2000 and 2010 (10 points) and 2010 and 2018 (8 points). California has experienced a similarly sharp decline in the White share of the electorate, dropping 15 pct points since 2000. This has resulted in California irresolute from a bulk White electorate in 2000 to a state where White voters were a minority share of the electorate in 2018 (60% in 2000 to 45% in 2018), though they all the same are the largest racial or ethnic grouping in the electorate.

Fifty-fifty with declines in all fifty states, White eligible voters still make upward the majority of most states' electorates. In 47 states, over half of eligible voters are White. The only exceptions are California, New Mexico and Hawaii, where White voters account for 45%, 43% and 25% of each respective state's electorate.

As reflected on the national level, Hispanic eligible voters have been the master drivers of the racial and ethnic diversification of most states' electorates. In 39 states between 2000 and 2018, Hispanic eligible voters saw the largest percentage point increment compared with any other racial or indigenous group. In three additional states – Alaska, Kentucky and Ohio – Hispanic voters were tied with another racial grouping for the highest increment. Five states that observed the largest growth in Hispanic shares in their electorates were California (11 percentage points), Nevada (10 points), Florida (9 points), Arizona (8 points) and Texas (8 points).

The number of Blackness eligible voters nationwide grew only slightly in the past 18 years. Yet, Black voters saw the largest percentage point increase out of whatever other racial and ethnic group in three states in the Southeast: Georgia (5 points), Delaware (iv points) and Mississippi (4 points).

As for Asian eligible voters, they saw robust growth in California (v percentage points), Nevada and New Jersey (4 points each) between 2000 and 2018. Nevertheless, their share increases paled in comparison to the Hispanic electorate'southward growth in those states. Overall, Asians saw their shares increase in the electorates of every state except Hawaii, where their share dropped past 4 percentage points. Still, Hawaii has the highest percentage of Asians in its electorate – 38% of all eligible voters in the state are Asian.

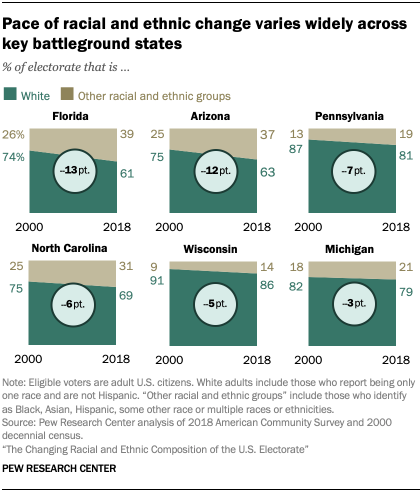

Racial and indigenous change among eligible voters in battleground states

As the 2020 presidential election draws near, these demographic shifts are specially notable in some key battleground states, where changes in the composition of the electorate could have an impact on electoral outcomes.5

Nationally, Florida and Arizona saw the 3rd- and fourth-largest declines in the shares of non-Hispanic White eligible voters. The White shares of the electorate in those states each stood at about six-in-ten in 2018, down from about 3-quarters at the showtime of the century. Four other battleground states – Pennsylvania, Northward Carolina, Wisconsin and Michigan – also saw declines in the share of White eligible voters between 2000 and 2018, though to a bottom extent.

In Florida, a country that has been pivotal to every U.S. presidential victory in the last xx years, the White share of the electorate has fallen 13 percentage points since 2000. At the same time, the Hispanic share of the electorate has gone up ix points, rising from 11% of eligible Florida voters in 2000 to 20% in 2018. During this same period, the Black share of the electorate in Florida has increased 2 percentage points and the Asian share has increased by 1 point.

Arizona, largely seen as an emerging battleground state, has seen substantial change to the racial and ethnic composition of its electorate. Hispanic adults now make up near one-quarter of all eligible voters (24%), an 8-point increase since 2000.

Several battlefield states have seen smaller – though still potentially meaningful – changes to the demographic composition of the electorate. In Pennsylvania, the White share of the electorate fell 7 pct points while the Hispanic share of the electorate rose 3 points from 2000 to 2018. And in Due north Carolina, a state that voted for Donald Trump in 2016 and previously went for Barack Obama, George Westward. Bush and Pecker Clinton, the White share of the electorate barbarous from 75% in 2000 to 69% in 2018. During the same time catamenia, the Hispanic share of the electorate rose to 4% (upwardly three points since 2000) and the Blackness share of the electorate rose to 22% (upwards i betoken since 2000).

Demographic changes could continue to reshape the electoral landscape in future elections. While Texas is not currently considered a battlefield state, demographic shifts have led some to wonder if the state could become more competitive politically down the route. In 2018, iii-in-ten eligible voters in Texas were Hispanic – that's up viii percentage points since 2000. During that same time, the share of White eligible voters in Texas fell 12 points, from 62% in 2000 to a bare majority (51%) in 2018.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/2020/09/23/the-changing-racial-and-ethnic-composition-of-the-u-s-electorate/

Posted by: northingtondarke1993.blogspot.com

0 Response to "When Does The Number Of Electoral Votes Change"

Post a Comment